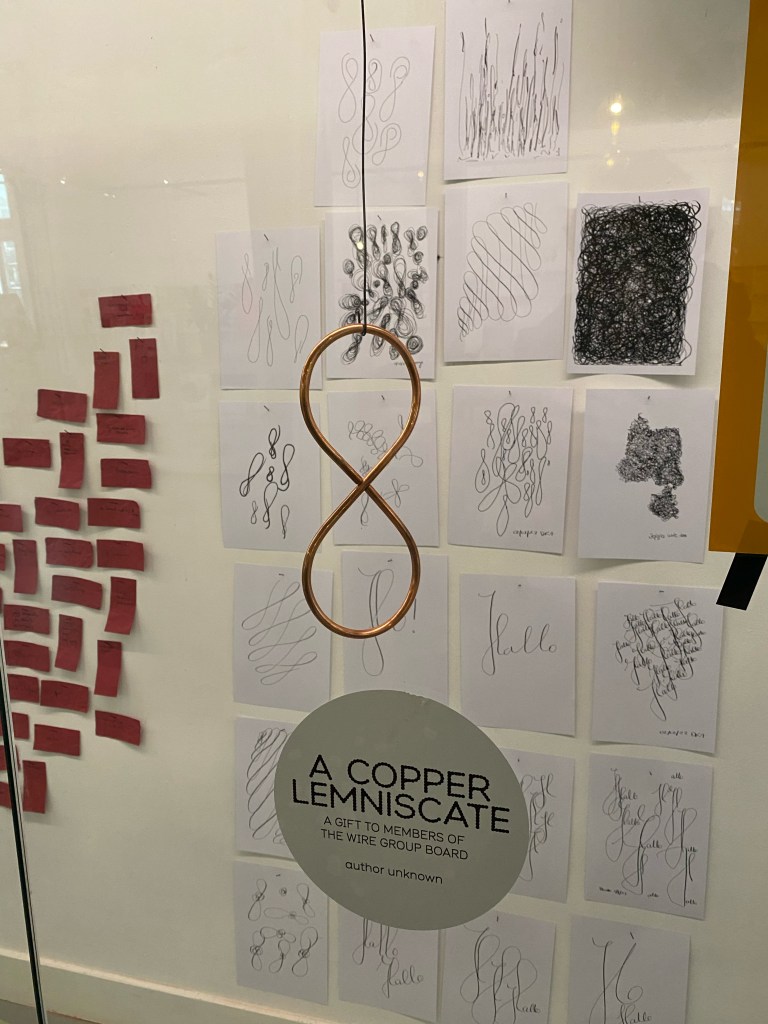

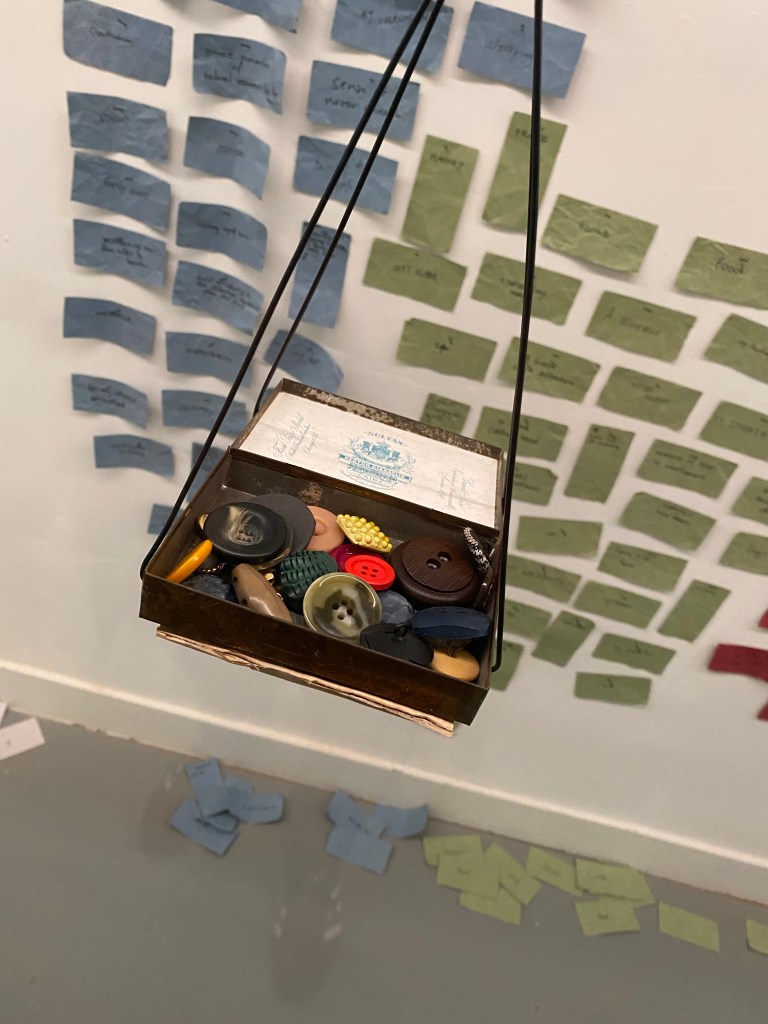

The last three weeks have been marked by finishing the lecture performance “Exchange”, together with Godelieve Spaas and Mojra Vogelnik Škerlj. The lecture performance is part of the larger Exchange Project, a collaboration between Breda-based dance company The100Hands, Godelieve Spaas & Avans University of Applied Sciences, and myself & Fontys Academy of the Arts. Last weekend, all elements of the Exchange Project – the lecture performance, the physical (dance) performance by The100Hands, and the exposition “Alchemy of Exchange” – finally came together at the festival “Van wie is de economie?” (“Who owns the economy?”), organised by Future of Work. A few images of the exposition:

The Lecture Performance

Before the official premiere of the lecture performance at the festival, Mojra, Godelieve and I performed a try-out a few weeks earlier at Fontys in Tilburg. As always with new work, I enjoyed both performances immensely: it is wonderful to see how a project suddenly comes to life and starts to grow, after months of meeting each other, collecting and trying out material, discussing, researching, and collecting. In this post, I want to share just a bit of an introduction to the work, and a few reflections and impressions that stayed with me after the performances.

In her opening monologue (the “lecture” part of the performance), Godelieve expresses her concerns about how the economy turns people, other beings and stuff into numbers; how people become workforces or market segments, nature becomes a commodity, and biodiversity a topic of percentages (“15% of this or that species has survived in the last X years.”). Narratives, stories, and entanglements become replaced by, and reduced to numbers, “so that we don’t have to feel, not as officials or politicians while making laws, not as people while buying and consuming, not as entrepreneurs while growing and striving for profit maximisation” (Godelieve).

We wonder if we can escape our roles, if we can rethink the capitalist myths and change our economic narrative? Can we bend the rules?

However, the problem with this first set of questions is that… they are too much. Too abstract. Too complex, and too much based on existing models. How to break them down without cutting the story into meaningless pieces that further dehumanise the notion of economy? How can we start talking about care and love in an environment that is about numbers? To explore this, we decided to look at the smallest unit of the economy: the transaction, the process of exchange. This became our main question:

Can we rethink exchange, the smallest meaningful unit of the economy, in order to change the system is a whole, one exchange at a time?

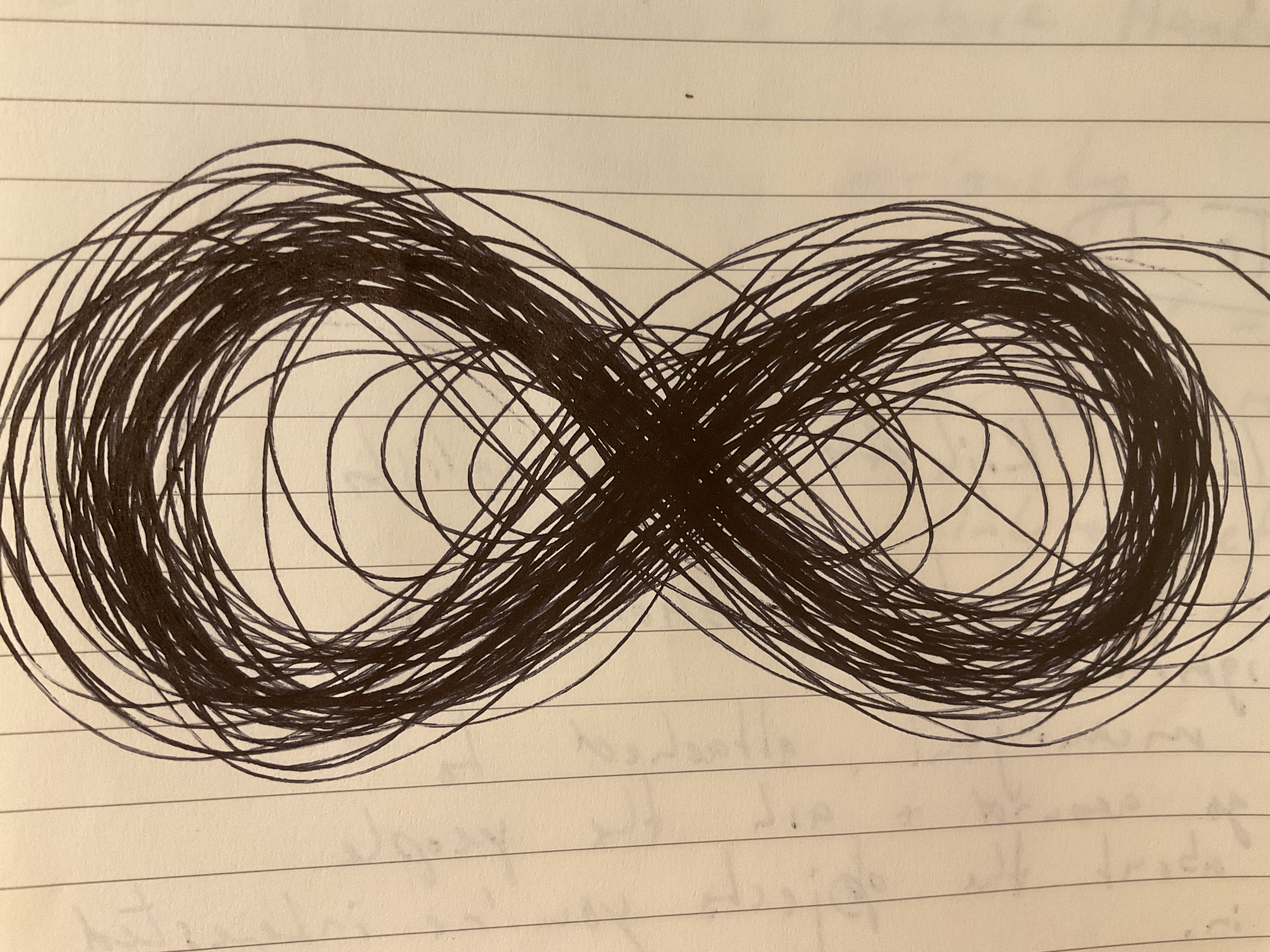

During the lecture performance, we share our explorations and reflections on this question with the audience through several stories, and let the audience be part of this exploration in the form of several assignments, exercises, and discussion. The leminiscate as a symbol of infinity and continuous exchange played a crucial role, as well as Godelieve’s youth love Hans, my passion for well-crafted pens made by small badge manufacturers, and Mojra’s encounter with an old man whom she took to a spot where he needed to be on her cargo bike.

Special moment 1: Herbie Hancock

When I think about Exchange, I cannot help thinking about improvised music, especially jazz. Oftentimes I wonder what the performance practice of Jazz (and with it other forms of performing arts in which improvisation or instant collective composition plays a role) has to offer us more in terms of interaction – and processes of social exchange.

Pianist Herbie Hancock tells a particularly intriguing story, which exemplifies what happens when materials are exchanged, sonic materials, notes, in this case – and when, all of a sudden, someone makes a mistake. So here’s the story, quoted from Hancock, from a performance of “So What”, during Miles Davis’ solo (for the entire interview, see here):

“The music was ON. Tony Williams was burning on his drums. Right in the middle of Miles’ solo, when he was playing one of his amazing solos, I played the WRONG CHORD. It sounded like a big mistake. And I did this, and I went… like this (takes his hands on his ears).

And Miles… paused. And then he played some notes that made my chord right. He made it correct. What I realise now is that Miles didn’t hear it as a mistake. He felt it was his responsibility to fid something that fit.

That taught me a very big lesson about not only music, but about life. You know. We can look for the world as we would like it to be as individuals, you know, make is easy for me. But I think the important thing is that we grow, and the only way we can grow is to have a mind that’s open enough to be able to accept, to experience situations as they are. Take whatever situation you have and make something constructive happen with it. That’s what I learned from that situation with Miles.

Interestingly, this situation has been taken as an example more than once by scholars as well, such as by philosopher Marcel Cobussen:

Musicians may also use a mistake as an inspiration for improvisation. Performance errors can also be treated as “compositional problems” that require instant, collective solutions: … Mistakes do not always need to be resolved, but may lead performers into musical areas otherwise undiscovered, and thus even strengthen the improvisation.

For Davis, the mistake was not so much a mistake as another unexpected event for him to react to. Hancock’s error was not so much rectified as used to push the solo into a new direction. In fact, one could say that Davis let his creative skills be put to the test by Hancock’s “wrong” chord.

(Cobussen 2017, The Field of Musical Improvisation, p. 100)

In many conversations and situations, I experience that people blame each other for their mistakes: either publicly in person or online, in personal conversation, or behind the back of those whose mistakes they blame. Almost as if exchange doesn’t happen at all after a mistake anymore. Or, in other words, as if an exchange after a mistake, productively dealing with a mistake, is more an exception than a rule. I wonder, what if we could use a mistake not only as something to make right, but also as an impulse for further exchange, and as an opportunity to push our conversations into different directions, just as Hancock’s mistake did with Davis’ solo.

Special moment 2: Hand-touch assignment Mojra

Another key moment for me was a physical assignment Mojra developed for the performance, which worked in and through touch. The participants work in pairs, sitting opposite to each other. In the first part of the exercise, one of each pair acts as receiver, the other as offerer (roles are exchanged later on). The receiver, with eyes closed, stretches one hand towards the offerer, who then gives a variety of touch impulses to the fingers, hand, palm and lower arm. Later, in the second part, both participants create a number of co-created shapes with their hands, arms and bodies, all based on the first part.

In the work with another participant, I experienced the exercise as beautiful and intense. Very gentle and careful (care-full?); slowly, softly, with patience. I was receiver first, so I needed to hold out my hand, close my eyes, and receive the various touchings by my partner-participant. It was fascinating getting to know each other slowly, through touch. In its slowness, the touching becomes very detailed; every small touch gesture becomes meaningful, carefully carrying the collaborative narrative forward.

When we took turns and I acted as offerer, I naturally took over this carefulness and gentleness. As a kind of habit, or certain way of acting emerged, in and through this carefulness. After the performance was over, sitting in the train reflecting, I wondered: What if we could take this/such kind of relational acting serious and think it through, towards other kinds of conversations and exchanges? If this was the habit with which we discuss organisational or policy issues or questions? A habit with which we talk across hierarchical layers in our organisations and institutions?

To finish this post and series of experiences of our performances, I like to share a part of the closing gratitude, written by Mojra and Godelieve:

We have come to the end of our joint search today. Together with Mojra and Falk, we explored different forms of exchange that might be a lever to change our economic system. We would like to invite us all once more to together pay tribute to everything that we have exchanged and everyone we have exchanged with today.

Consciously or unconsciously, visibly and invisibly. All the Experiences, stories, and expressions we shared that none of us could have given without the families and communities we are part of. Without the lives of and memories of our ancestors. After all, it is their dreams that we are now living.

Contributions also that we could share due to our experiences in our different contexts. The city and street we live in, the ecosystem we are part of, the living and non-living beings that surround us. All those beings and contexts we want to thank because they make us and this research possible.

It is not only our history and environment that carry us. The dreams we have for our children, communities, and the earth also shape our conversations and actions. Future generations were already at the table here, and we are also grateful to them for their contribution. For what they will become one day.

1 Comment